4 Costly Myths About World Heritage

One of 21 U.S. World Heritage sites: Montana's Glacier National Park.

How can the issue of Palestine end up costing American jobs in New Mexico? Or hobble protection of great places worldwide? That tortuous path winds through four common American misconceptions about UNESCO World Heritage sites, plus Congress’s own version of the law of unintended consequences.

To help clear things up, the U.N. Foundation sponsored an educational Congressional briefing about World Heritage last week in Washington D.C. On Monday Dec. 3, I joined the panel, led off by Assistant Secretary of State Esther Brimmer. Our goal was to help Congressional staffers spread the word about how World Heritage works, why it benefits the U.S. economy, and what role is really played by UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Brimmer was there because the Administration is unhappy about the 2011 U.S. funding cutoff to UNESCO—done for reasons having nothing to do with World Heritage. More on that shortly.

In a Capitol conference room, our capacity 80-person audience heard the following points.

As of its 40th birthday, the World Heritage List names 962 sites—natural, cultural, and mixed—in 157 countries. Sites must be “of outstanding universal value” and protected under local law in order to be considered for “inscription” on the List.

The U.S. has 21 sites, disproportionately low for our size. (France has 38, China 43.) Part of the reason involves four misconceptions that I have addressed in similar presentations around the country this year:

The Four Myths

1. World Heritage was dreamed up by non-Americans. No. While people from many nations contributed to the process that led to the World Heritage Convention, it was two Americans who put forth the concept of an international list to honor and help protect both cultural and natural sites of significance to all humankind. Joseph Fisher, a Democratic congressman, and Russell Train, Republican director of the Environmental Protection Agency under Richard Nixon, propelled it through to adoption in 1972. (Bipartisan efforts worked in those days.)

The first country to sign the Convention? The United States of America.

2. The U.N. runs it. Easy to assume—after all, the common term is “UNESCO World Heritage site.” But no, the World Heritage Convention is a separate treaty, with a separate membership. It designates UNESCO as the agency to administer the World Heritage list, but the World Heritage Committee, selected by Convention signatories, makes the decisions about it. UNESCO’s World Heritage Center and a host of international specialists in nature and culture advise the Committee.

3. UNESCO picks the sites. No. Countries must ask to have a site added to the list. The site must already be protected under local laws in order to be eligible. After extensive evaluation, sometimes including recommendation for additional protection, the World Heritage Committee votes on whether to add it. Each country submits its candidates for inscription on a “Tentative List.”

4. UNESCO controls the sites. No. This is the dangerous one, the sovereignty myth—that a country gives up sovereignty over the inscribed site. During a controversy in the 1990s about environmental threats that put Yellowstone on the World Heritage “In Danger” list, the Park Service reported hearing from alarmed locals who sincerely believed that Wyoming was about to be invaded by U.N. forces in black helicopters and blue helmets.

The reality: The entire staff of the UNESCO World Heritage Center in Paris is about the same as for a well-run boutique resort. Their job is to monitor almost a thousand sites around the world and evaluate hundreds of new submissions. They are overwhelmed. They have neither the authority nor the means to enforce anything. They can advise, they can complain, and as an absolute last resort, they can ask the Committee to enact its worst possible sanction: Deletion from the list. In 40 years, that has happened only twice, for sites in Oman and Germany. The whole idea is to find a solution, so that deletion doesn’t happen.

The Cost of the Myths

None of this would matter that much, except for America’s politically shrill anti-U.N. fringe, whose disproportionate clout kept the Senate last week from ratifying an innocuous treaty for disabled rights, based on U.S. law already in place. (The argument was that under the proposed treaty, the U.N. could maybe somehow prohibit American home schooling. Eh?)

This noisy fragment’s UNESCO paranoia makes a difference. It enabled an amendment to the Preservation Act that makes it virtually impossible for a multi-owner historic district in the U.S. to apply for World Heritage inscription. By contrast, Mexico’s 31 sites—10 more than the U.S.—include many historic districts and towns with thriving tourism economies, such as Guanajuato and San Miguel. The U.N.-haters have had the effect of discouraging promotion of existing U.S. World Heritage sites as well.

Power of a brand: After the town of Albi, France received World Heritage status in 2010 tourism jumped 52 percent.

For the American economy, it’s a shoot-ourselves-in-the-foot scenario. World Heritage is so successful that its brand attracts tourists from just about everywhere outside the U.S. To these foreign visitors, a World Heritage designation means, “This place has been vetted. It really is of outstanding value. We want to see it.” For the U.S., that’s especially important for less famous sites, such as Chaco Canyon or Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, and for the tourism jobs they support.

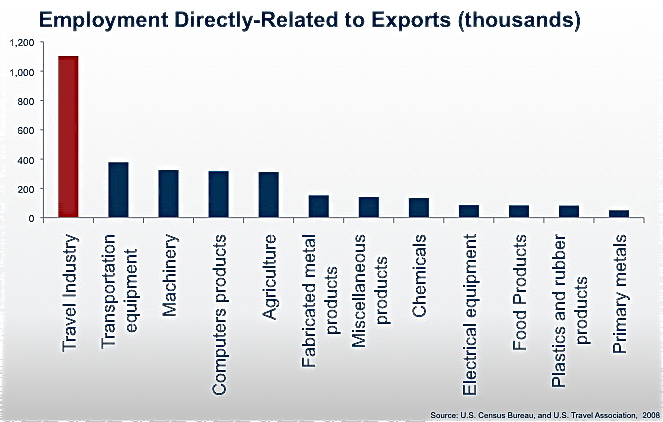

At last week’s event, David Huether of the United States Travel Association laid out the statistics on the value of foreign tourism. Basically, foreign tourists on average spend more than domestic tourists, stay longer, and thus create travel-industry jobs for the U.S. His data showed at least a million jobs related to inbound foreign tourism.

U.S. jobs related to inbound international tourism, considered an export because foreign visitors buy a domestic product: a U.S. experience.

Stephen Morris of the National Park Service, which oversees the U.S. World Heritage program, rounded out the panel. He explained the intricate process for a locale to propose itself for inscription by applying for the U.S. Tentative List.

What’s Palestine Got To Do With It?

Assistant Secretary Brimmer had asked to speak at the Monday event in part because the Administration is seeking a waiver on the automatic funding cutoff for UNESCO. That’s where Palestine comes in. Back in the 90’s Congress enacted laws requiring the U.S. to eliminate funding for any U.N. agency that admitted Palestine, and last year—two decades later—UNESCO members voted to do just that. To paraphrase Brimmer, this sort of automatic tripwire ultimatum effectively puts policy decisions in the hands of the other guys, not the U.S.

Before the cut-off, U.S. dues had covered about 20 percent of UNESCO’s budget. The unintended effect now has been to shortchange the World Heritage Center—the same office that has been raising the alarm this year about destruction of cultural World Heritage sites by extremist Islamist rebels at Timbuktu in Mali. Thus Congress has in a way put itself on the same side as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Probably not what they had in mind.

Outstanding Universal Value to Humankind

World Heritage has plenty of bumps and blemishes—inconsistent inscriptions, politics (what doesn’t?), and occasionally sloppy procedures, as with archaeology issues raised earlier this year and inadequate resources for helping sites cope with tourism. But if we ask, what if it had never existed? No question but that the program has helped save and protect great places all over the earth, and kept it a richer place for all of us. Americans can pride in their leadership role 40 years ago.

To Congress, last week’s message was simple and politically digestible: World Heritage sites attract foreign tourists. Foreign tourists create U.S. jobs.

As for the red-herring “threat to U.S. sovereignty,” it’s a nonissue, a “nothing muffin” in the words of the Washington Post. All that UNESCO can do about a problem at a World Heritage site, whether Yellowstone or Timbuktu, is throw a light on it and suggest solutions.

That’s exactly what they are supposed to do.